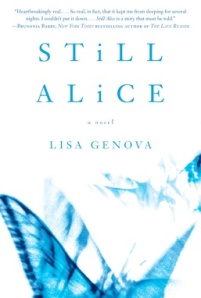

Often sad, sometimes frightening, always compelling, Still Alice, the story of a Harvard professor with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, is told with a clear-eyed compassion which keeps the reader racing to turn the pages. I was afraid this novel would be depressing, but amazingly it isn’t.

This is not a caregiver’s handbook; it’s fiction, but it will instill in any reader who knows a person with dementia a more profound understanding of how to better communicate and simply be with them. For those fortunate enough not to have a friend or family member affected by the disease, Still Alice offers insight into how our own brains function…or not. If the true measure of a book is whether it changes your perception of some part of the world you live in, then this is a great one.

Still Alice begins with Professor of Psychology Alice Howland tracking down her equally academic husband’s glasses for him as he tries to get to work on time. While she feels the usual wifely exasperation at John’s inability to find his own keys, etc., she also empathizes since she has recently noticed that she’s losing things too, such as her Blackberry, which she later finds plugged into its charger beside her bed. Alice chalks this up as normal for a multi-tasker who’s fifty years old. The reader finds it more ominous since author Lisa Genova has opened the book with a single dramatic paragraph saying that “there were neurons in her head…that were being strangled to death, too quietly for her to hear them.”

After Alice goes running and can’t find her way home from Harvard Square, a place she knows like the back of her hand, she begins to worry that her forgetting is more than just a menopausal woman’s typical memory difficulties. Without telling anyone in her family, she begins the process which results in the diagnosis of early on-set Alzheimer’s. As she reads a list of activities which will be affected throughout the progression of the disease, she finds the items: “Has given up reading. Never writes. No more language.” Alice is a specialist in neurolinguistics, the study of the mechanisms of language.

She looked at the rows of books and periodicals on her bookcase, the stack of final exams to be corrected on her desk, the emails in her inbox, the red-flashing voice-mail light on her phone. … She had experiments to perform, papers to write, and lectures to give and attend. Everything she did and loved, everything she was, required language.

In clear, lucid prose, Ms. Genova shows us how Alice’s family responds to the diagnosis, how she tries to compensate for the symptoms as she continues to teach at Harvard, how her colleagues avoid her once the diagnosis is made public, and, most important, what Alice herself is thinking, feeling, and struggling with. In a very unusual and gutsy choice, the author tells the story from Alice’s point-of-view. The reader lives in Alice’s mind as that mind betrays her with increasing frequency.

And yet, there are gifts the disease gives her. As she loses the ability to absorb words, her sensitivity to body language increases. Her relationship with her youngest daughter improves dramatically. She no longer bases her entire identity on her achievements at work. She comes to understand love on a deeply felt level.

Interestingly, the author spent a year querying and being rejected by agents who said no one would want to read a novel about Alzheimer’s. Frustrated, Ms. Genova decided to self-publish the book, which is so well researched it received the stamp of approval from the Alzheimer’s Association. After a year of selling Still Alice out of the back of her car, Ms. Genova was contacted by an agent who sold it to Simon & Schuster for half a million dollars. Now the book is a New York Times bestseller.

Hi Nancy,

Wow. Thank you so much for this beautifully written review! I’m so glad Still Alice moved you.

Best wishes,

Lisa

Gosh, how wonderful to hear from the author herself! I think STILL ALICE is an amazing book (just in case you didn’t get that from the review– LOL). BTW, this review will also appear in my women’s club’s newsletter. (I cheat and use it twice.) Feel free to quote me! 😉

Thanks for stopping by!

Nancy

Your review is compelling. It is now on my list of “to read” books.

Let me know what you thought of the book when you get a chance to read it. I’m recommending it to everyone I know!